Photo: Christmas market in the Altstadt-Mitte, Freiburg. (Source: author’s personal documentation, 2023)

In December, people across Europe begin to get busy with various Christmas celebrations. When I was conducting field research in Europe in December 2023, Sechseläutenplatz in Zurich, Switzerland, had been transformed into a beautiful Christmas market. People flocked there with friends, family, relatives, or partners. They enjoyed various snacks amid the glittering lights and falling snow at night. Meanwhile, during the day, Werdmühleplatz was “transformed” into an attraction where children and their parents sang various Christmas songs under an artificial fir tree. The atmosphere at the Weinachtsmarkt (Christmas market) in Freiburg, Germany, is not much different. At these markets, there are vendors selling glühwein (mulled wine), which is a Christmas specialty, bratwurst (sausages) and bread, trinket craftsmen, musicians, circus rides, and so on. The vendors or performers are set up in kiosks or other temporary locations, so they can be dismantled when the Christmas market is over. Meanwhile, buyers or visitors are free to choose which items or performances they want to enjoy.

Photo: People take shelter from the snow at one of the timber huts at the Sechseläutenplatz Christmas market in Zurich. (Source: author’s personal archive, 2023)

Photo: Primary school children from Freiburg who were allowed to perform at the Singender Weihnachtsbaum (Singing Christmas Tree) event at Werdmühleplatz square, Zurich. (Source: author’s personal documentation, 2023)

The festive atmosphere of Christmas markets is indeed a special attraction for anyone in Europe during the month of December. In Indonesia, we can see a similar atmosphere in the bustling Ramadan markets, especially as the time to break the fast approaches.

Markets involve not only relationships between people who are already acquainted, such as relatives, friends, partners, or family, but also between people who may not know each other. As in any market, there are sellers and buyers. However, the sellers of glühwein in Zurich and Freiburg do not necessarily know me, who has come all the way from Yogyakarta, and vice versa. The kolak seller who came all the way from Bantul to the Ramadan market in Jogokariyan, Yogyakarta, may not necessarily know the buyer who came home from Jakarta. Even though they are strangers to each other, their relationship is mediated by the exchange of goods and services for money. The seller adds profit to their sales calculations, while the buyer is charged with this additional cost in order to get what they want in return. This calculation is a logical consequence of the practices of competition and accumulation brought about by today’s market capitalism system. This is what then conditions a reciprocal relationship that we take for granted as a form of “market” organization, to the point of becoming the mainstream economic practice of today. No matter where production takes place, who does it, and why they do it, as long as they are in such a reciprocal relationship, sellers and buyers can meet and interact.

So, what would a “market” look like if it were organized in such a way that sellers did not add profit calculations and buyers were not charged additional costs for the goods and services they wanted or needed?

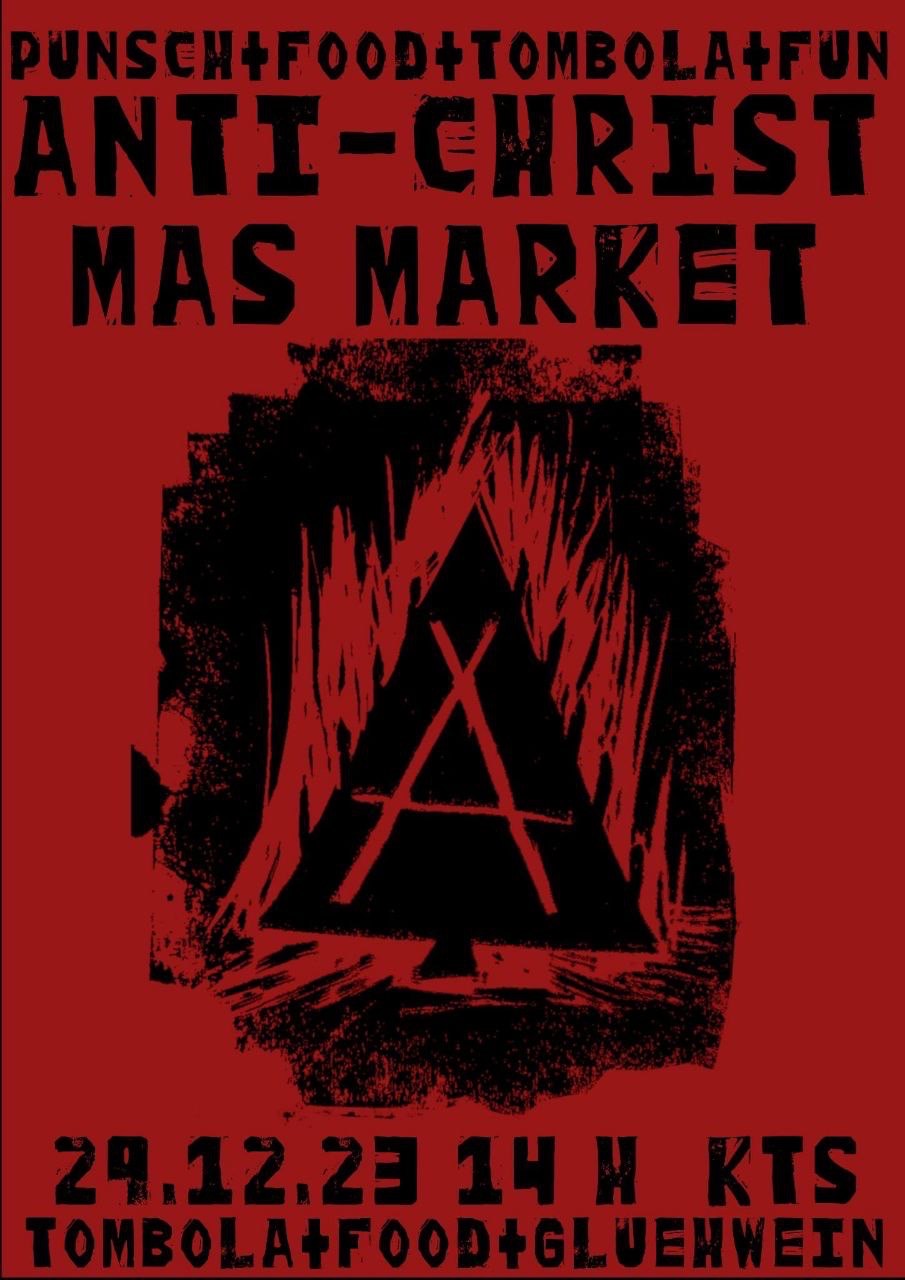

In an old building on the outskirts of Freiburg, the Christmas market can be organized differently. This old building is managed by a group of people who identify themselves as autonomous, or adherents of anarchist ideas and practices that developed in West Germany from the 1970s to the 1980s. They named the building KTS, or Kulturtreff in Selbstverwaltung (self-managed cultural meeting place).

On December 29, 2023, they held an event called the “Anti-Christmas Market.” When I visited, there were various foods and drinks, just like at a typical Christmas market. There were also items displayed on tables. However, it turned out that none of the food or items needed to be purchased. Everyone who came to this event could bring their own items to donate or exchange for other items. Food and drinks could be paid for through a donation scheme, or enjoyed for free. At that time, I tried glühwein and free hot soup, unlike at Christmas markets, where you have to pay. People who came here chatted with each other, played cards, enjoyed music, and did other fun things. The exchange at a typical market based on profit did not work here.

Another time, I visited a room in the building called the “Free Shop.” Andreas, one of the activists who is active in KTS, accompanied me to the room. There, he put down some items that he had brought because he hadn’t used them in a long time. Rather than letting them go to waste, he thought it would be better to give them to the Free Shop in case someone else needed them and could use them. In that room, I took a carabiner and donated one of my T-shirts. Everyone can take the items they need here and donate something in return if they want to. Whether at the “Anti-Christmas Market” event or the “Free Shop” room, the benefits and social exchange through various activities are aspects that far exceed economic profit and loss calculations. Even in a country that pioneered modern capitalism, like Germany, criticism of mainstream economic organization continues to be practiced.

Photo: Poster for the “Anti-Christmas Market” event at KTS, Freiburg. (Source: adapted by the author from the KTS Telegram group, 2023)

This experience made me rethink the concept of “market” in general, as well as the mainstream economic practices that dictate the lives of people in Indonesia today. Currently, for example, Indonesia is one of the largest suppliers of palm oil to the global market, accounting for 50% of the total supply. However, at the same time, Indonesia ranks third after Russia and Thailand as a country with unequal wealth distribution (Li & Semedi, 2021). Market practices in today’s capitalist system produce much more inequality for the majority of the world’s population and contribute to huge profits for a select few. The question is, why do we seem to be stuck in a system that produces inequality time and time again? Why are markets and macroeconomics not organized through a system that produces social benefits and exchanges, without being entirely dictated by profit?

Reference

Li, Tania., & Semedi, Pujo. (2021). Plantation life: corporate occupation in Indonesia’s oil palm zone. Duke University Press.

Authors: Muhammad Harits Hibatullah